Today’s post represents is joint project between prof Alessandro Canossa and me (Lizzie Stark). We delivered a talk on playable characters in larp for the Playful Virtual Characters Workshop at Northeastern in 2014, and Lizzie translated it into the text below. At the session, we presented a brief history of larp and a snapshot of larp styles. Then we started talking characters..

Characters are, perhaps, the essence of larp. They are a vital part of even the definition of larp. To larp is to portray a character. The ways in which larpwrights and players produce those characters—and the way those methods and tools connect to a player—matter. Characters need to fit the storyline and allow for customization. In larp, the player becomes the character and controls the character in a way that is unlike other media.

Drawing on our own experiences playing, reading, and researching larps and tabletop roleplaying games, we looked at existing games and tried to figure out what commonalities they had when it came to developing characters. In this piece, we break it down in two ways—approaches to character creation, and general sorts of tools used to develop characters. Many games mix and match several approaches and several tools. The more we thought about it, the more commonalities emerged.

CHARACTER CREATION APPROACHES

Asking players to generate new materials.

This approach gives players a jumping off point and asks them to create characters. Here, some or all of the burden of creating a character that fits the setting falls onto the players. In some traditions, getting players to generate some of the world’s fiction is known as “co-creation” and overlaps a bit with the next approach.

The benefit of asking players to generate new materials is that it can help players feel invested in their characters and thus in the game. The downside is that co-creation always takes more time than just handing someone a sheet and saying “go.” Sometimes people get intimidated, or stuck when asked to create things out of whole cloth. Another downside is that sometimes players may create characters that poke at the boundaries of the game world or don’t fit exactly with the setting.

Examples:

- A “hot seat” warm-up, where players get into small groups. One person sits on the hot seat, and the others fire questions ranging from simple and small (“What’s your favorite color?”) to important and deep (“What was your relationship with your mom like?” “What’s your darkest fear?”) at the focus player for a set period of time. This allows the player on the hot seat to generate a bunch of fiction about their character, and there’s no pressure—they can change that before play if they wish.

- Traditional fantasy campaigns, where players come up with their back story on their own.

Providing materials for players

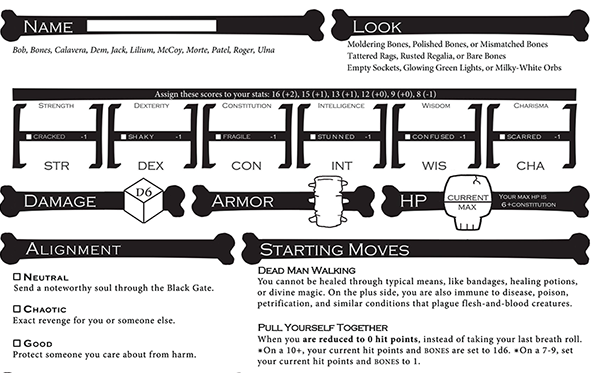

In this character sheet from Dungeon World, players are given choices of name, look, and alignment, helping them quickly customize their characters

In this approach, the larp writer creates content and basically gives it to the players. Sometimes, they players may be offered limited choice to create buy-in, but the bulk of the burden of creating characters falls on the organizers.

The advantage of this method is that it makes set-up fast. The downside is, of course, that you miss out on the buy-in that co-creation can create. Another downside is that if you give someone a role they are not suited to, they might find it difficult to play without other suitable warmups.

Example:

- Pre-written character sheets of a few paragraphs, that tell players about their characters’ pasts and presents.

- Character sheets that contain some level of choice for the player, but are basically predetermined. For example, if a character sheet has a slot for current mood, and then asks the player to choose from, “cheerful, miserable, indifferent” by circling one. (See Dungeon World character sheet above.)

Relying on preexisting information, social norms, or archetypes.

This approach lets the real world do some of the heavy lifting when it comes to character types. If I tell you we’re going to play a larp about a court drama, you already know that the characters will probably be a prosecutor, defendant, and judge.

The advantage of this approach is that it transmits a lot of knowledge without anyone having to say or produce anything. The disadvantage is that using this approach binds you to people’s real world expectations and stereotypes, with all the limitations that can carry.

Most games function on this premise at least a little—the game creator generally needs to specify the ways in which the game world is not like (players’ typical ideas about) our world.

There are lots of ways to let the real world do the heavy lifting for you. Here are a few examples:

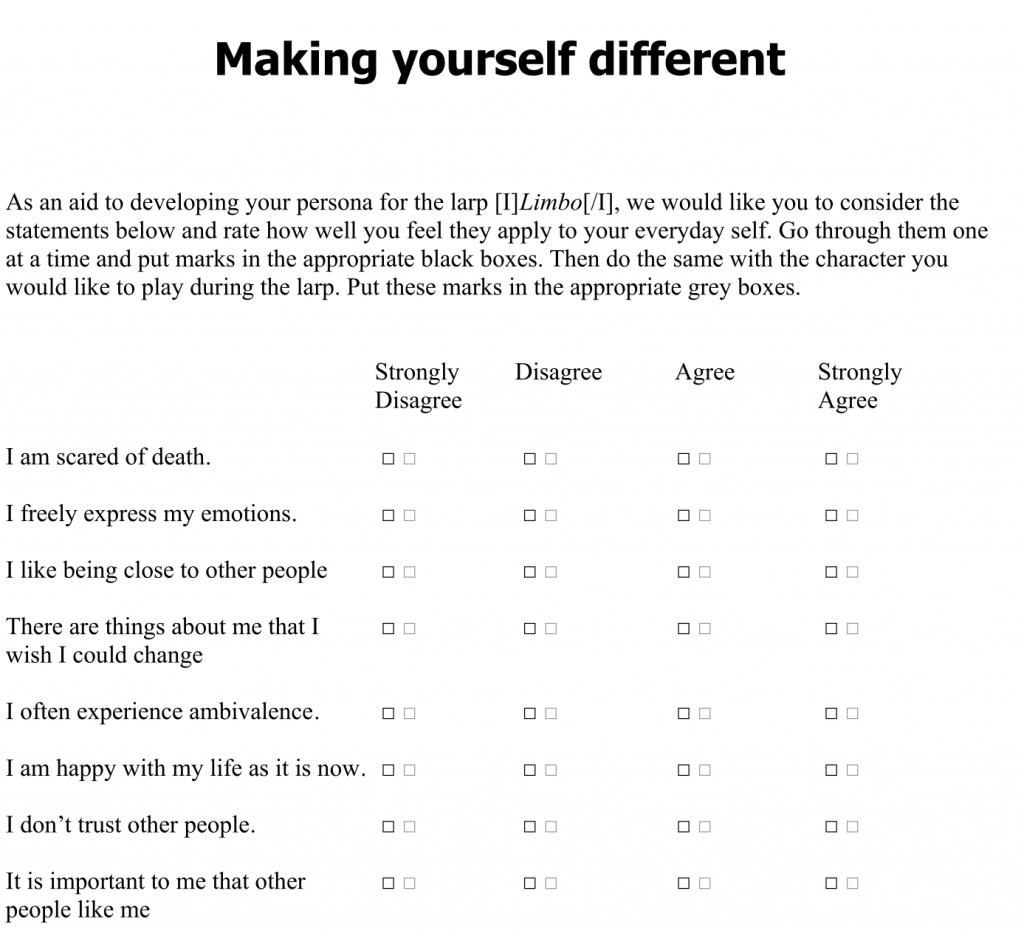

- Asking players to strongly bring themselves to the character. You’re like yourself, but slightly different. Limbo by Tor Kjetil Edland uses this approach deliberately.

- Rely on the heteropatriarchy. The jeepform classic Doubt by Frederik Axelzon and Tobias Wrigstad relies on this. Doubt is about two straight actors in a failing relationship who are also playing a failing relationship onstage together, and that’s all the players know about them to start. Most people have extensive cultural context for failing straight relationships, so the characters are easy to play.

- Rely on myths, tropes or other common cultural artifacts. Most players will be familiar with the pitfalls of rom-coms, the myth of Adam and Eve, and the plot to Star Wars.

CHARACTER CREATION TOOLS

These tools represent actual tools we’ve seen used in various larps as part of the character creation process, grouped together by what aspect of the character they are focused on.

1. Defining a character through relationships

Basically, this means building a character through who they are to others—perhaps they are a mother, a business associate, an ex-best friend, that guy in the office who monopolizes the coffee machine, the ex-lover whom one cannot stand but for whom one still carries a torch, etc.

By defining the relationships a character has, that character can come into focus.

Practically-speaking, there are many ways to define a character through relationships in actual games. In When Our Destinies Meet by Petter Karlsson and Morgan Jarl, players draw character relationships out of a hat, sometimes in several combinations. In Jason Morningstar’s tabletop game Fiasco, the players select character relationships from lists, restricted by the use of dice. In Screwing the Crew by Trine Lise Lindahl and Elin Nilsen, players toss a ball of yarn to make a web, stating a new relationship with each toss.

2. Defining a character through setting.

Setting plays an important part in character creation. Vampire squids might not belong in a serious courtroom drama set during WWII. The setting of a game always determines its characters by setting parameters about the game world. Beyond this, standard level, some games use setting even more actively.

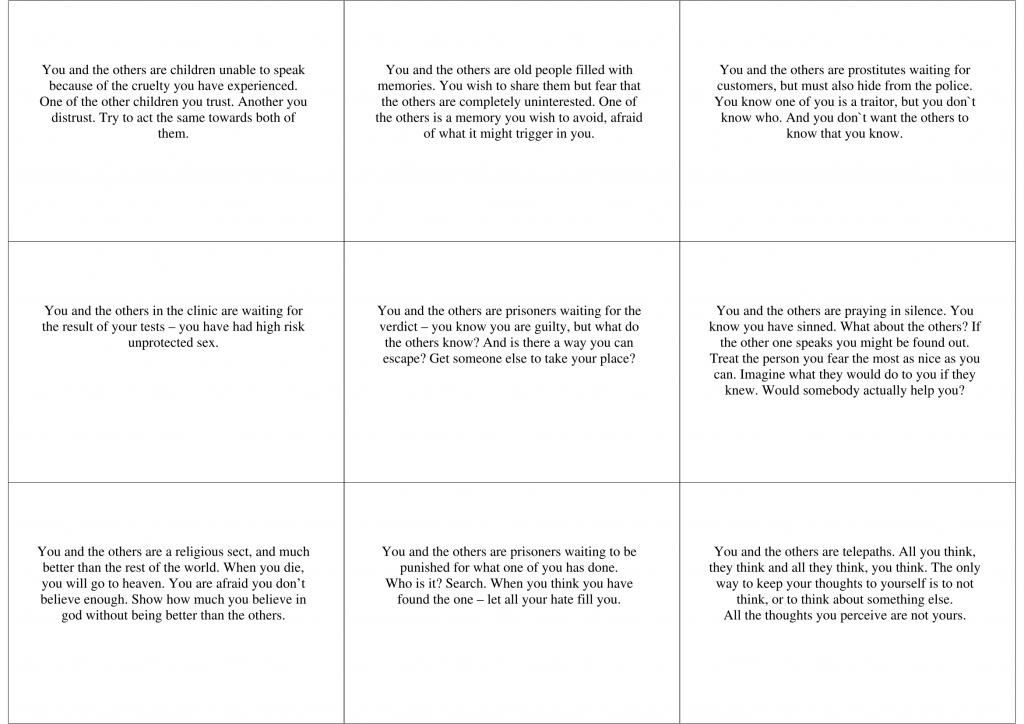

For example, in Before and After Silence by Fredrik Hossmann and Matthijs Holter, each participant draws a card with a different setting on it. During the game, which is played in silence, they interpret all action through the lens of that setting and act accordingly.

3. Inspiring characters through status and group membership.

This uses a character’s overall place within a community to help clarify who they are. This isn’t merely a subset of the “defining characters through relationships” tool, as not all relationships have clear dynamics within them. Status is a way of talking about a character’s place within a larger social group rather than the intimate interior relationship of two characters.

The larp Play the Cards by Tyra Larsdatter Grasmo, Fride Sofie Jansen, and Trine Lise Lindahl is about high school. Each character starts out with a playing card affixed to their chest. The card’s suit indicates which clique a character belongs to (the hearts are the popular girls, the spades are jocks, clubs are alterna-kids, and the diamonds are the nerds), and the number of the card indicates social standing.

In Trine Lise Lindahl and Elin Nilsen’s Screwing the Crew, the players portray a group of friends that has met through some activity, and the players work together to define what it was. The results of that reverberate through the game.

By the same token, many larps ask characters to line up according to status during the workshop, to help players understand more about their character. During In Residency, Lizzie’s larp about an artists’ colony, for example, characters line up by self-perception of fame, and by actual fame as perceived by the outside world.

4. Defining characters through physicality and language.

Sometimes, the starting place for who a character is begins in the grounding of the physical body and speech patterns. The physicality of the body creates feelings and moods, which then create characters.

Tue Beck Saarie and Jesper Bruun’s larp In Fair Verona revolves around a little-Italy ghetto of New York in the 1930s, except the only way the characters know how to interact is through tango dancing. During the workshop we—this larp is actually how the authors of this piece met—danced like slump-shouldered introverts and chest-puffed-out extroverts, using the physicality to help build our characters.

In Nina Rune Essendrop and Simon Steen Hansen’s White Death, there is no language, only physicality. During the workshop players receive a physical restriction upon which they build their characters—perhaps you can only move in a planar jumping-jack motion, or your character’s head must loll to the side while keeping fingertips toward the ground.

In What Happened in Lanzarote by Aslak Tirera, the writer communicates characters’ personalities through tone and speech patterns embedded in the character sheets.

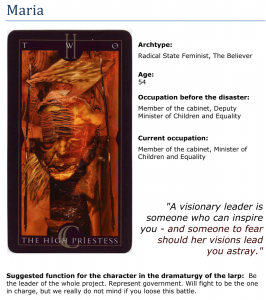

5. Defining a character through permanent archetypes.

Defining a character through an archetype gives players a sense of the type of character they are supposed to play while leaving the details up to them. Here, the archetypes work as a cultural shorthand to transmit information about what sort of characters are OK to create from designer to player. This technique is pretty common in roleplaying games.

The simplest example comes from Dungeons & Dragons, where characters are grouped into archetypes like “thief,” “bard,” or “paladin.”

In Trine Lise Lindahl, M. Raaum, and Tor Kjetil Edland’s Mad About the Boy, a tarot card represents each of the characters, for example.

In Maria Bergmann Hamming and Jeppe Bergmann Hamming’s Sarabande, uses archetypes, such as the Jester, the Idealist, and the Grey, in combination with other techniques, to help players create their characters during workshop.

6. Inspiring characters through artifacts and production value.

Sometimes, inspiration comes from things you can feel, smell, taste, and touch. This can make a powerful appeal to the senses of the player, as the items used to inspire the character are then used in play.

Graham Walmsley’s Marinara features food. participants write some tasting notes about an ingredient in marinara sauce, and use that to inspire their character.

Tue Beck Saarie and Jesper Bruun’s larp In Fair Verona crowd-sources the character inspiration. Participants bring a prop that is period appropriate for the 1930s, then choose an item from the collection to inspire their character.

In campaign larps such as James Kimball’s Knight Realms, some players get inspired to develop a character after purchasing a particular item of clothing or foam weapon.

7. Defining a character through play, including rules and structures.

No character starts out fully formed, but characters become fully formed during play. A piece of paper with some backstory on it is not a character—the character is the living breathing thing embodied by players as they play. Who the character gets fleshed out during play, and the events of the game will shape them.

Sometimes this takes an ambient form—another character asks a question at a cocktail party that causes a player to create a backstory for their character on the fly. Maybe a character begins a game with three relationships, but one clearly becomes most important during the course of play.

Sometimes this is heavily determined by the rules or structure during the game, for example, through mandated backstory scenes, or by playing the same scene in different years and tracking how the character changes. Perhaps a the plot of the game forces a stark choice onto the character that will shape them.

Shaping a character through structures and social interactions, whether through a sandboxy design, or through structured freeform scenes is at the essence of most larp design.

Conclusion

This is not an exhaustive list of techniques and methods used to create characters for larps, rather, it’s a start at exploring how designers create playable characters. Most of the tools seem to function as a tether, a connection between the real world and the world of the game. The physical prop that inspires a character becomes a tangible reminder during play. The relationships between characters and players developed in the workshop translate into game play. Physical restrictions define the motion of the body in the game world.

Games Mentioned

When dates or locations are in doubt, I’ve listed the place and date of the first run known to me, or the published version best known to me.

Axelzon, Frederik and Tobias Wrigstad. Doubt. Hobro, Denmark: Fastaval, 2007.

Bruun, Jesper and Tue Beck Saarie. In Fair Verona. Copenhagen: Knudepunkt, 2011.

Edland, Tor Kjetil. Limbo. Oslo: Chamberlarps, 2007. Republished in Larps from the Factory, Trine Lise Lindahl, Elin Nilsen, and Lizzie Stark, eds.. Copenhagen: Rollespilsakademiet, 2013.

Edland, Tor Kjetil, Trine Lise Lindahl and M. Raaum. Mad About the Boy. Norway, 2010.

Essendrop, Nina Rune and Simon Steen Hansen. White Death. Copenhagen, 2012.

Grasmo, Tyra Larsdatter, Fride Sofie Jansen, and Trine Lise Lindahl with Katrin Førde. “Play the Cards.” Larps from the Factory, Trine Lise Lindahl, Elin Nilsen, and Lizzie Stark, eds. Copenhagen: Rollespilsakademiet, 2013.

Hamming, Maria Bergmann and Jeppe Bergmann. Sarabande. Hobro, Denmark: Fastaval, 2013.

Hossmann, Fredrik and Matthijs Holter. “Before and After Silence.” Larps from the Factory, Trine Lise Lindahl, Elin Nilsen, and Lizzie Stark, eds. Copenhagen: Rollespilsakademiet, 2013.

Karlsson, Petter and Morgan Jarl. When Our Destinies Meet. Vilnius, Lithuania: Larpwriter Summer School, 2013.

Koebel, Adam and Sage LaTorra. Dungeon World. RNDM Games, 2013.

Kimball, James C. Knight Realms. Sparta, New Jersey: run continuously 1997-2016.

Lindahl, Trine Lise and Elin Nilsen. “Screwing the Crew.” Republished in Larps from the Factory, Trine Lise Lindahl, Elin Nilsen, and Lizzie Stark, eds. Copenhagen: Rollespilsakademiet, 2013.

Morningstar, Jason. Fiasco. Bullypulpit, 2009.

Stark, Lizzie. In Residency. Boston, MA: Stark Scenarios, 2014

Tierra, Aslak. “What Happened in Lanzarote.” Larps from the Factory, Trine Lise Lindahl, Elin Nilsen, and Lizzie Stark, eds. Copenhagen: Rollespilsakademiet, 2013.

Walmsley, Graham. Marinara. Ocean City, New Jersey: 2016.

_____

Alessandro Canossa is Associate Professor within the College of Arts, Media and Design at Northeastern University. His current work employs psychological theories of personality, motivation and emotion to design interactive scenarios with the purpose of investigating individual differences in behavior among users of digital entertainment. His research agenda can be broken down in three main areas: a) design and development of digital environments aimed at eliciting specific affective and/or behavioral responses; b) developing behavioral analysis methodologies that are able to account for granular spatial and temporal events, avoiding aggregation; c) design and development of visual analytics tools that can enable any stakeholder to produce advanced statistics and datamining reports.

Lizzie Stark is the author of two books. Leaving Mundania, about larp, and Pandora’s DNA, about the world of inherited breast cancer. Her journalism and essays have appeared many places, including The Washington Post, Daily Beast, and i09. She also designs games and serves as the main author of this blog. But you probably knew that.

LeavingMundania.com owes its existence to the continued support of many wonderful Patrons. If you enjoyed this post, consider supporting it with a few dollars and joining the conflagration of awesome people underwriting my blog on Patreon.

Pingback: Literary and Performative Imaginaries – Where Characters Come From - Nordiclarp.org