I spent most of my time at E3 standing behind an enormous sign that read “#Feminism.”

E3 is a video game trade show, where new games are announced, game developers network, and press circulate freely. It’s also an enormous spectacle. An at-scale New Orleans street based on a scene from the game Mafia III complete with picturesque benches, was built near the entrance to one of the expo halls. The Resident Evil franchise provided an enormous creepy mansion. Ubisoft built an actual stadium, complete with balcony seating. Expensive lighting rigs and the flicker of the pervasive digital screens illuminated the massive hall. Throbbing sound effects emanated from all directions, at a not-quite- deafening, but impossible to escape level. At one point, ‘Lil Wayne even played nearby. Live.

The amount of money on display is staggering. The booths take millions of dollars to set up, and the pace of the networking is relentless. Everyone here has a platform, a game, a media outlet to hawk.

And I was no exception. I make analog games that take place in meat-space, not on a screen, in which your friends’ voices provide the dialogue, your creativity directs the plot, and your brain is your virtual reality machine. My roleplaying games live in a pile of perfect-bound dead trees, not something that runs on a console or computer. I never thought I’d find myself at an industry-only video game event like this.

Across from Ubisoft’s hundred-foot long bank of video screens was the IndieCade booth where, each year, this international festival of independent digital and analog games curates a showcase of around 30 selections for E3. This year is IndieCade’s tenth anniversary.

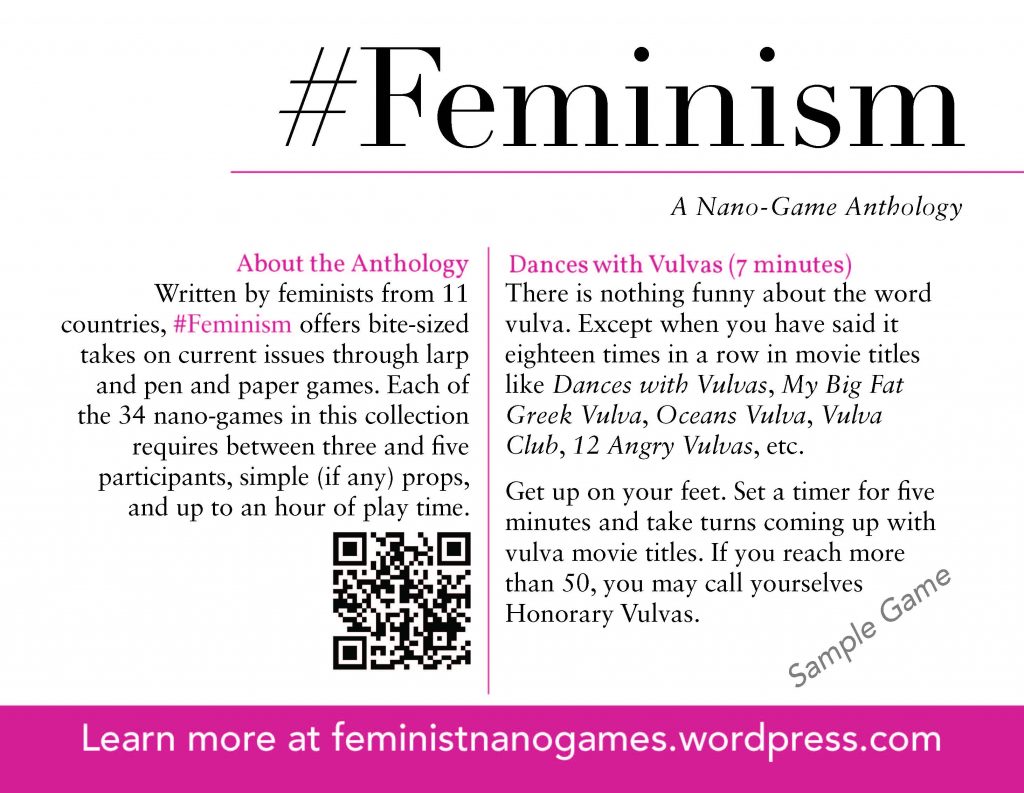

#Feminism, an anthology of 34 small analog games by designers from 11 different countries, nabbed one of the lucky spots in IndieCade’s booth. All the games last less than an hour, require three to five participants, and tackle an issue in contemporary feminism that mattered to one of our designers. The collection has lighter games about selfies and soap operas, as well as heavier games about grey zone sexual encounters and domestic violence.

I contributed a game to the anthology. I also edited it, together with Misha Bushyager and Anna Westerling, with a strong assist from our talented designer, Shuo Meng. A larger international collective of feminists from all over the world provided playtesting, business savvy, and other support.

This is how I found myself standing behind a banner that read #Feminism, at an event for an industry not known for welcoming women, especially feminists, into its ranks. I attended with Strix Beltrán, a member of the #Feminism collective, who writes for video games and works as a corporate diversity and inclusion consultant. A lifelong fan of video games, she spent most of her time at the trade show in various states of nerdgasm.

Still, given the anthology we were there to represent, we didn’t know what to expect. For the most part, we were pleasantly surprised.

Despite the fact that I grew up playing freeware games and point and click adventures, despite the fact that the man who would become my husband and I conducted part of our then-long- distance relationship through Diablo II raids, and despite the fact that I still lose significant hours of my life to Civilization, I don’t consider myself a gamer.

There was little at E3 that caused me to reconsider that. I didn’t see much advertising I’d consider to be misogynistic, but I also didn’t see many ads that included female characters or otherwise indicated that video game companies cared about having me as an audience member. The composition of the conference—overwhelmingly white and male—didn’t upend my expectations.

At the #Feminism display, Strix and I didn’t encounter anything but pleasantness and support. Lots of men stopped by to tell us that they supported our venture, both for themselves and because of the tough stories they’ve heard from their women colleagues in game design. Even a few exhibitors from well-known media and entertainment companies made a beeline for our booth and made feminist confessions like, “Not everyone at our company is on board yet, but we’re trying to work harder on diversity and inclusion.” Or, “If you do one of these for digital games, would you let big companies contribute?”

More surprising was the parade of men stopping by with feminist complaints—mainly that the new Legend of Zelda game didn’t deliver on the playable female characters it teased at in early previews. And of course, we got the inevitable questions: “I am confused about what feminism is. Can you tell me?” “Forgive me for saying this, but it’s a man’s world. Why is feminism important?” We were, of course, happy to start a discussion.

On the first day at lunch, Strix sat down at an empty table in the food court. Soon after, a group of eight or nine men sat down at her table, literally surrounding her, while having a loud and explicit conversation about VR porn, with the apparent intent to intimidate her. She’s not easily cowed. After asking repeatedly, she discovered that they were exhibitors for a well-known company and lodged a complaint.

By day two, women were swinging by our booth because, as one woman told us, she needed a break from the overwhelmingly male environment of the expo hall. We met a feminist game designer and scholar from Japan, interested in our project because she deals with an environment even less friendly to female developers and feminist design than the US market. A couple women remarked on positive changes within the expo, like the fact that this year saw fewer “booth babes”—paid models in skimpy outfits—than previous years.

But it does say something about the state of the industry that the question we got most frequently was, “Has anyone attacked you yet today?” They weren’t even worried about our physical and emotional health and safety over the long haul, but about this very morning, this very minute. That even a scrappy, crowd-funded print project with a $7,000 budget evoked that sort of concern unsettled us. “I didn’t get assaulted or yelled at during this event,” is a pretty low bar to vault.

For the moment, at least, we’re content with our E3 experience. Strix got a sweet collectible Zelda coin and earned the corresponding T-shirt of her dreams. We made a ton of people say the word “vulvas” in different movie titles as part of our demo game by Swedish designer Kajsa Greger, and we rubbed shoulders with lots of cool indie designers.

Most importantly, we had great discussions about feminism with gamers from all over the world—and people really did want to talk about feminism in relationship to their own lives as well as to the industry.

We started to fantasize about next year. Bathed in the glow of a thousand video temples, we imagined having our own palace, as big as the fabricated paradises the major companies enjoy. You’d find ours by the word “Feminism” suspended from the ceiling and lit up in neon. A ten foot tall statue of bell hooks would greet you at the entrance. It’d be a place to rest for a while, to talk if you needed to, and most importantly, to play an amazing new slate of feminist games.

Hey, a girl can dream, right?

_____

LeavingMundania.com owes its existence to the continued support of many wonderful Patrons. If you enjoyed this post, consider joining the conflagration of awesome people underwriting my blog on Patreon.

If you launch a kickstarter to get that statue of bell hooks made, well, in the words of Philip J. Fry, shut up,and take my money.